I am waiting for a friend of mine to arrive so I can feel less crazy. I’ve been sleeping poorly or not sleeping at all for a multitude of reasons, which I wrote down in a text to another friend when they asked me why I haven’t been sleeping. Well, what they really texted was “insomnia?” because they are going to be a very good doctor one day and I can tell because they ask direct and blunt questions.

At 9:46am Central Time, I get a notification from my Chani app that says, “Ready, set, go: The Moon is trining Mars. Channel the momentum by doing the thing you keep putting off.” I don’t read it until I roll out of bed at 2pm of course (wow, remember when I said the Station would turn me into a morning person? And then I almost went blind in one eye and my sleep schedule got fucked even more? That was pretty funny) and once I do, I start turning over stones in my head. What could she mean by this! I’m putting off just about everything! What’s the thing? What now?

I don’t actually believe in astrology, not in any way that matters. My estranged ex-best-friend who I quote all the time used to say, “When you tell me what should happen, it keeps me from imagining what could.” It was a wise and astute observation. They had (and have) a lot of those. Still, I have the Chani app because a lot of my other friends are really into astrology. They draw comfort from it and I draw comfort from them.

Actually, now that I think about it, I think my ex-best-friend was referring to tarot? It’s funny. I read tarot. I’m really good at reading tarot. I think another aspect of my sleeplessness is coming from my lack of ritual. To give you a general idea of what my life looks like right now:

The coldest room in the house is sequestered in the far side of the upstairs, farthest from the staircase. It has a flatscreen Fire TV on top of a treasure chest, which I’ve unceremoniously dumped my first Gramma’s Sausages packer on like some kind of flaccid altar. It’s the one I need to repair because it’s coming apart. It’s been coming apart for quite some time. I have the patch kit in my backpack, but just below the treasure chest is everything I brought with me from Seattle. I was in Seattle for two weeks, you see, right after leaving Cranberry Lake. DG and I took a train from Minneapolis to get there.

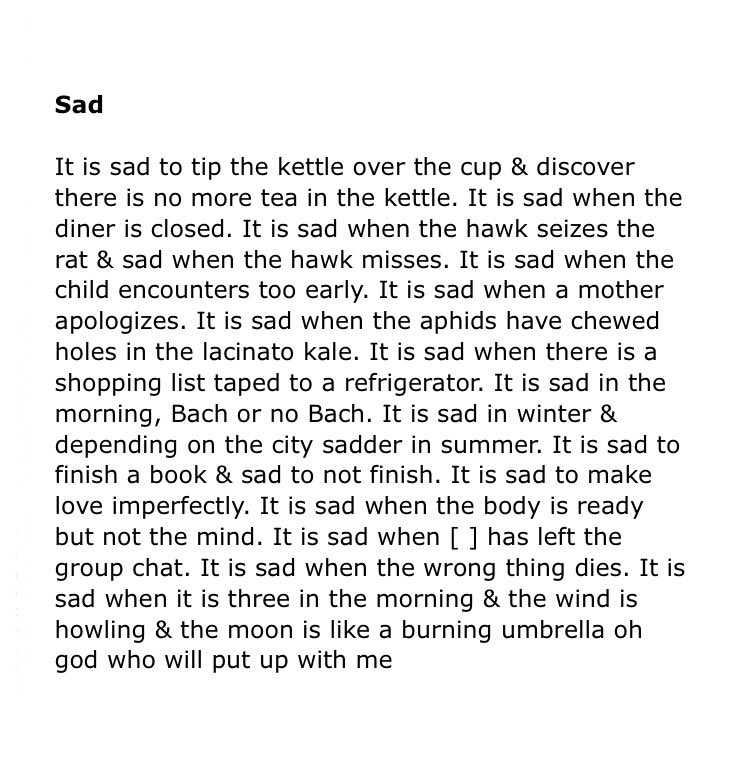

So much has happened. I keep wanting to update you as it happens, and then more stuff happens, and I sit in front of a blank screen, exhausted, wondering what portion of myself to give away until I get sick of myself and annoyed with my tone of voice, and all that fills my brain is this poem by Jeremy Radin:

Specifically that last line, on repeat: oh god who will put up with me. oh god who will put up with me. oh god,

who will put up with me?

I am afraid of the answer. My father puts up with me. My siblings do. We are, of course, capable of making each other feel awful in that special way only your family can. We are also the only ones who can build each other back up all the way, or at least, that’s how it feels to me, even as time slips through my fingertips and everyone pairs off and absorbs partners into the family like the Blob eats American teenagers.

Ugh. Even now, I bristle at the idea of posting this. But part of me—call it my “higher self,” if you’re extra annoying, call it logic and reason, call it the cold analysis of one who has been told the same things by the same people over and over again, enough to form a pretty good assessment of their place in people’s lives, God help them—part of me feels there’s something important in showing you this particular bloody and raw self-inflicted verbal embargo. Something about telling you that, as much as I love to portray myself one way, there is another way beneath it that often rears its head. There is insecurity, and annoyance, and all the ugly, non-grammable things that we either keep to ourselves or spread around in miserable bouts of sarcasm or untenable anger.

My nephew is not yet a year old, but his temperament reminds me of my own. He is happy, smiling, genial, a complete ray of sunshine and warmth, and then all at once, crying, screaming, angry, frustrated. I do this, too, and I wish I didn’t. Going, going, gone off the rails. I have a way of filling the room with pressurized malaise. I can make the house bend and sway. Now, he’s a baby, and has absolutely no control over himself, but I’m an adult. I do.

My friend has just pulled up in their boxy little car. My mood has improved by a lot.

Right. You know those memes that are like, girls will spend one hour with their friends and post “my heart is so full?” I’m girls.

We talked about a lot of stuff. It always goes back to sex and death and what it means for our community. Also the apocalypse. But right now I want to divert from my friend and I for just a moment. I want to talk about our grandma.

There is a kind of self-consciousness I’ve dealt with lately around grief. I think because I feel that word has fallen to the level of other overused words, like “emotional labor,” “toxic,” “trauma,” and the like. I brush against the word “grief” and a legion of tenderqueers rear their shorn heads to tell me I’m “valid” and I can be as selfish or all-encompassing as I need while I deal with my little bit of sadness. While I tend my broken land.

When our mom passed, all my older brother Smokii could talk about was grief. He is a poet and his world is full of people who need to talk about everything. People who hold space for catharsis and complexity. People who make complicated emotions more accessible to people who, say, just sort of mindlessly scroll and might need a bit of care in their lives. I love my brother and I love the work he and his peers do. I also cannot be that. I cannot do that. Radical vulnerability, when boiled down and reduced to bite-sized morsels to please an algorithm, is a deft art I do not possess. I am, to quote my father, “a real piece of work.” These spaces and this movement and indeed, this moment, often find me a pinned moth, splayed and ever-beautiful, my pain never concluding, my life never free to rot and fall apart.

If that sounds dramatic, it’s because it is. But I need to exorcise the drama here. Otherwise, it comes out in inconvenient ways. In “toxic” ways.

Before we lost our grandma, I lost a friend. I wasn’t going to talk about that here, but one of my screenshots, which is from Kat Mills Martin’s Substack, MAKING, opens with an acknowledgment of the things we feed in spring that die in summer. All the potential futures we lose. Thank God, my not-a-friend is still alive. They just got fed up with my bullshit. Don’t comfort me for saying that, please. Don’t say I’m in the right. For one, you don’t know the situation, and for two, I’m not putting myself down. I have bullshit. You have bullshit. We all do. We all have the capacity to be selfish, cruel, callous, and ignorant. Even abusive. Sometimes the people we love realize they don’t need to take this from us and they move on because they know they can take something (anything!) more congruent from someone else.

After my friend cut me off, I couldn’t stop thinking about them. I didn’t understand how much of a fixture in my life they were until the option to text them whatever silly thing I wanted to share was denied. We had been growing closer, closer, closer all spring, and then summer came and we grew apart with sudden swiftness. In the aftermath I can see how many mismatches there were, of course. I can know I wouldn’t have been good for them, long term. We need to spend time with the people who actually care for us the way we want to be cared for, and I wasn’t caring for them the way they wanted.

Which brings me to our grandma.

See, the other self-consciousness happens when someone dies. I feel like I don’t have the right to be sad. I wasn’t there enough. I wasn’t good enough. I wasn’t nice enough or present enough. I couldn’t have loved them enough because here I am, tearing my way through the universe, youthful and self-centered and navel-gazing, meanwhile the whole time, this person’s getting older. And the guilt of my absence keeps me from reaching out, which deepens the absence.

Hey.

Call them.

I don’t care. You shouldn’t, either. If they’re still alive. If you’re even a little bit cool with each other. If it’s been awhile or it’s only been a day.

Call them.

I’ll try to do the same. I’ll try. But we try and we try and we do bad and we drop the ball because we’re people. But we need to try.

So, I’ll try to tell you about her. I won’t go into too many details. She lived. She was very beautiful. She was mean and everyone knew her meanness deeply. She had the prettiest smile I’d seen. When I was a baby, she said she was going to take me away (as a joke) and I bit her hard, hoping she’d drop me. She was married for her entire life to a handsome white man named Arnold who loved her so profoundly, so earnestly, and so openly, that I didn’t realize until much, much later that heterosexual couples are often miserable in each other’s presence. That misery is normal. That his utter devotion to her wasn’t.

My baby brother called Arnold “Grandpa Arnold” when we were very small, and it stuck. I remember that moment very clearly. We were in the Meskwaki Casino, in the buffet dining area. I used to eat so many shrimp I would make myself sick. One of my uncles told me something about how if I ate shrimp tails, they’d cut me up inside, and I got so scared, I stopped forever, but at this point in time I only ate shrimp, tails and all.

Misko was bald or close to bald, with a little tuft of copper hair. He loudly proclaimed something I don’t recall, but I remember he punctuated it “Grandpa Arnold” with such assuredness, everyone laughed. That was how he was, when he was small. Blunt and loud and brusque. Deanna, hitherto known to us girls as “Auntie Deanna,” then became “Grandma Deanna,” a title I never once asked her how she felt about, because it became one of those indomitable, forever-things. She would always be Grandma. He would always be Grandpa.

She was very Catholic. She talked to me a lot about Saint Kateri Tekakwitha. Sometimes it was because she was working on an icon of the saint for her church, and she knew I was an artist, so the long, arduous, holy process of icon-making became our conversation topic. Sometimes it was because the more fucked up my skin got from eczema, the more insecure I grew, and she noticed and told me Saint Kateri was covered in scars. This mattered. In these memories, I am always in her kitchen, touching the soft magnets she and Grandpa Arnold have on their fridge.

Even with all of this in my mind and in my hands, I worry it’s not enough. And that’s ego. Again, a quote from my estranged ex-best-friend: “You are both more and less important than you think.” They were right. They were often right.

At the funeral, all us godless heathens who carry her blood shared furtive glances amongst ourselves, while the mere three Catholics in our family held it down in prayer. The glances, roughly translated: what are we supposed to do now? All these rituals. All these atonal songs. Did that soprano up there know our grandma? Did we?

Of course we did. Of course I did. And the proof lay in the way we all looked at each other in silent acknowledgement of all that goes unsaid when someone you love dies. All the bit-back imperfections. All the things we can’t say.

My friend and I sat on the porch, where I write this now, and talked. I like listening to them talk. Even or especially when they get on my nerves, although I worry about writing that, because I know we live in a time when insecurities sting extra hard because everything’s falling apart. I think they know, though. I think they know I love them and they drive me up the wall sometimes.

We were talking about our tribe. We’re both from White Earth. We’re both… chaotic, shall we say? And on the wind there came a sense-memory that definitely wasn’t mine. Someone who was built a little bit like me, sitting on a porch with someone who was built a little bit like my friend, and these people were talking about the same shit we were discussing, just a long time ago, on the same land, in a different moment, a different context. I stared at my friend then as they spoke. I tried to memorize their hairline and their teeth and their bizarre little mannerisms, all the things that draw me in, all the things that annoy me.

Grandma Deanna had dementia. Alzheimer’s, they call it, after someone dies. I still don’t know why they do that. Why they wait until the person’s gone before they name the disease. I suppose that’s a Googleable question.

A couple years ago, a different Catholic mother and I stayed up very late. She was from Panama and English was her second language. She was a little bit elderly, so I treated her with reverence, though her children were my age. I was curled up on her daughters’ couch. She sat at their little round table, her golden-brown hair illuminated by a single overhead lightbulb. The rest of the apartment was in shadow.

She told me the way her mother staved off memory loss was her rosary. Every night, she prayed the rosary and named everyone she ever loved or hated. Everyone who helped her at the grocery store or the library, everyone in the hospitals, her daughters, her sons, her grandchildren and great-grandchildren.

“When I call her,” said the mother, “her mind is sharp as a diamond always. It is because she prays. It is because she works and walks with God.”

Grandma Deanna was pious and precise. If anyone worked and walked with God, it was her, even near the end. I know there are other forces at play. I know there are things beyond our control, things that steal your mind away no matter how much you roll the rosary across your knuckles, no matter how good you are.

I know she probably remembers everything now. Everything she forgot. Everything she didn’t know she could forget.

The man who ran her funeral said we know Dee is now in the company of saints. For some reason, I imagined that company to look a lot like this. Like a porch on a cool summer’s night and everyone knows you well enough to say exactly what you need to hear. Like all your friends saying, “I remember, you told me,” and you nod and say, “I did tell you that already, didn’t I?” And the sun goes down and the streetlights come on and you don’t have to sleep alone ever again.

Leave a comment