A slow-burn retrospective on genocide

Summer is irreducible. This doesn’t stop us from trying. I could write about the moments that define summers past. I could play the magician and make you know without knowing the before-and-after of each solstice. I could, but I won’t.

There was no transition period for us here. One week, we were being pan-seared on the pavement, the next, I had to put on “the uniform,” the standard Pretty Girl outfit I’ve poured my body into every September since seventh grade: oversized sweater, short-shorts, red Converse. The parts of the sum matured, I guess. The sweater isn’t a joke anymore, but a carefully knitted warm beige number with a full-color embroidered buck standing on the edge of a river across the chest. The shorts are embroidered, too, by me, “ur gay” written in fuzzy pink lettering. An accusation, a challenge, exposure therapy for the guys who flinch every time I look at one of my friends with love in my eyes. The Converse are no longer canvas, but suede and leather with red piping. This morning, in the Blue Moon Too, a beautiful girl with ash blonde hair down past her waist and pecan brown skin smiled up at me shyly. She looked younger than me by a lot, or maybe she was just holding herself like that.

“I love your outfit,” she said. Her voice was clipped and restrained, like she was trying to swallow the words before they could be properly heard. She held her mouth in such a frightened way. I smiled warmly at her and said something stupid and honest back, “I love your hair,” or something along those lines. She didn’t hear me. She took a breath and said, resolute and somber, “I love people who just be who they are and show the world. Don’t care what nobody says.”

I glanced over her symmetrical piercings, one on each nostril, one in each dimple. I hoped she could hear what I meant when I said “me, too.”

A chill ran through me. In the seventh grade, a different girl, also with ash blonde hair and brown skin, had come to me with a similar declaration about my own perceived independence. I had bristled at that girl back then, because I had attitude problems and everyone knew it.

“People say shit about me?” I had demanded. My hair was long, so black it looked blue, and fell in my face like the Grudge.

“I didn’t mean anything by it,” my classmate had said. Later, she apologized, and what was worse, she meant it.

I wore Converse for my whole life because my dad wears Converse. For the past couple years, I haven’t, choosing instead to lace into my grandfathers’ respective combat boots or the tattered pair of original rubber Doc Martens my dad and I scored at Trader K’s in Ithaca, years before it closed. Thirty bucks and they’d been made in England for real! Otherwise I have these Nike N7s, the Fly chunky boots I stole from Ava, and the black and white checkered platform shoes my mother wore every day while she was pregnant with me. If you were the psychoanalyzing type, you’d have a field day with my closet.

This summer, I primarily wore the Doc Martens and the N7s. The N7s are sort of honey-beige and spattered with bleach and paint stains. Unsure why. The model prior to these ones was made to look and feel like cartoon moccasins. Mine look like regular shoes, just… earthier? They give me another inch or so of height I don’t need and make me feel like I’m exercising when I’m not. The Doc Martens always blister me and I keep thinking I need to buy gel inserts, but I never remember this when I’m in a place that sells them. Anyways.

Near the end of June and my residency at Cranberry Lake Biological Station, I was in Terrance’s cabin with a bunch of professors plus my dad. We were all visiting and laughing and I was starting to have an allergic reaction to Terrance’s cat, so I stood up just as we got on the subject of my shoelaces. My Docs had already chewed up one pair of shoelaces, so I walked around with replacements. Then one of the replacements got fucked while I was on my way back from the hospital, so I needed new ones. I informed the group of this because I love small talk and complaining about useless things.

“Wait,” my dad said, “you already have mismatched shoelaces, the hell is the matter with you?”

One of my shoelaces says YOU ARE ON NATIVE LAND over and over and over again, it’s true. I think my little sibling has the other one.

“Yes, and I’ll keep it as long as we’re on Native land,” I said, voice dripping with irony the white people definitely didn’t pick up on. “Enough scrutiny. Goodnight.”

I walked back to my cabin, pressing my “native land” foot into the spongy earth as hard as I could, as if empty words by a goth-ish vaporwave brand making bank on stating the obvious could wake up the sleeping giants beneath. As if my sole and my soul were one. As if putting one foot in front of the other could fix any of this.

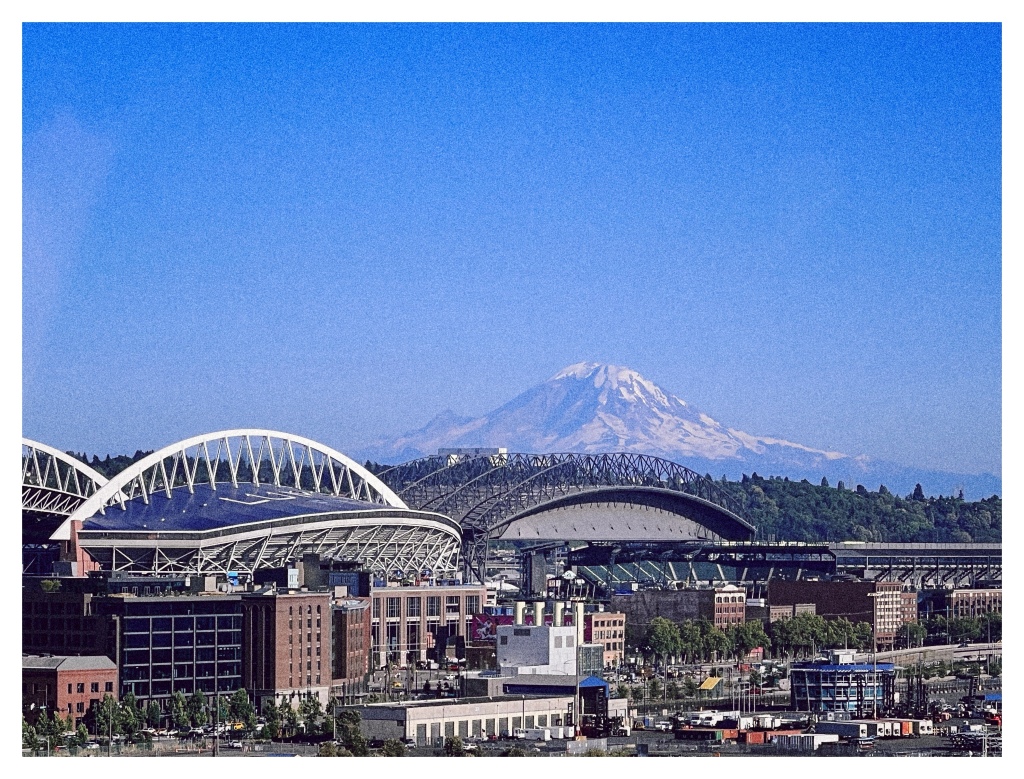

For a split second, this summer threatened to define itself as the one where I almost went blind. Then it was the summer of ill-advised hookups. Then it was the summer of taking the train. The summer I made my baby nephew really mad because I wouldn’t let him electrocute himself. The summer Taylor and I took the girls up into the big ferris wheel above Seattle. The summer I became beautiful. The summer I turned mean.

I was on the phone with my mother today after pulling into my aunt’s driveway. I had a laundry list of things that needed done and choices I had to make and I was still rotating the weekend in my head, trying to examine it from all angles. I’d gone to see Godflesh with Phil at the Baltimore Soundstage before performing with Andie, Kamya, LouLou and Genocide at the Daughters of Lilith’s inaugural art show opening, Venusian: an Exploration of Femininity Through the Planetary Lens of Venus.

When I’d shown up, everything was chaos, but the show went off beautifully and I rode the high of my new life all the way up to Ithaca, where I was the maid of honor at one of my best friends’ big gay trans wedding. Around 9pm that same night (this was Saturday) I pulled up at the Sacred Root Kava Bar to perform as Bogo La$ik on a bill with STCLVR, Prayer Rope, Phantom Project, Magnetic Coroner, and Compactor. Sunday, I finished a tattoo design commission in the Watershed while a group of elderly white Ithacans played Irish jigs loud as hell, Taylor squinting across the table at me in sensory overload and mounting irritation. Monday I was back in Baltimore for the Igorrr show, which might have just ruined all live music for me, because I can’t imagine anything being better than that.

I am telling you all of this because I’m going to tell you something else, but the thing I want to tell you is awful. Tom King writes about that in his book, the Truth About Stories. He tells this heartbreaking story about a friend of his who was made to recount all the traumas he’d endured, part and parcel with colonialism, and the more he rehashed this narrative, the sicker he got. Like the spirits that feed off our pain wanted more pain to feed off of. Like they were cultivating him.

So when I talk about anything extra fucked up, I cloak it in the banal and the funny and the stupid. All the things we forget about when we have those big, defining moments. There’s always a wedding. We don’t see the settled disputes, the nights the couple has sex in such a way, they feel like they’re going to dissolve into each other, the nights they don’t but they know they’re one beast anyways. The fridge magnets, the cold shoulders, the financial stress, the inside jokes, the periods and the hospital visits and the traffic jams. We just see the wedding.

Same goes for a funeral. We go for the dead. We pin them to the ground. We decide they’re in heaven or privately acknowledge they’re probably just nowhere. We do the protocols for our lodges and we cover the mirrors and photographs and we do not speak their names. We weren’t them, so we’re not there for all the days they spent feeling lonely, or angry, or stitching moment to moment with taste and touch and hunger and want and fear.

After Grandma Deanna died, I got mean. I got mean in a foreign way. The meanness did not come from me. It hunted me. It scoped me out. It did its research. Then, when it realized I was safe, it entered my mouth and now it inhabits my head, my throat, my bones.

In the car, on the phone, I wondered aloud to my mother if it had come from her. Our grandma.

“Like she couldn’t bring it with her to heaven,” I said, “so she shed it like a snake sheds its skin.”

“Holy fuck,” my mother said, in the tone she uses whenever an idea resonates. Then she gathered herself. “I mean, yeah. Heaven doesn’t need that shit.”

“I feel like someone handed me a gun,” I said. “I don’t know how to use it and I’m scared it’ll go off when it’s not supposed to.”

“Just sit with it,” my mother said. “It’s a useful tool. It’s a good thing. It can be a good thing.”

I told her at the Igorrr concert a guy tried to come onto me, but he looked too young for me, so I waved him off and it was like I’d used the Force on him. He was there and then he wasn’t, jettisoned away by the wave of my hand, out of my purview, out of the venue. I felt terrible. I felt powerful. Suddenly, everything I said or did had an extra bite to it, an extra weight. The pressure made me desperate. I looked at Phil often and tried to anchor myself on his familiarity, but my eyes swam with a cloying darkness I’ve observed in other people who are needy and cruel and don’t know how to control it.

This morning I borrowed Phil’s copy of This Thing Between Us by Gus Moreno. I read most of the first bit at the bar in Blue Moon Too. When it got to Thiago tracing his own lineage, marked and marred by hurt, abuse, and murder, I shivered, because this summer hadn’t only been the summer of embodiment, death, sex, meanness and beauty. It had been the summer when a handful of people had, unprompted, told me their version of my father’s conception.

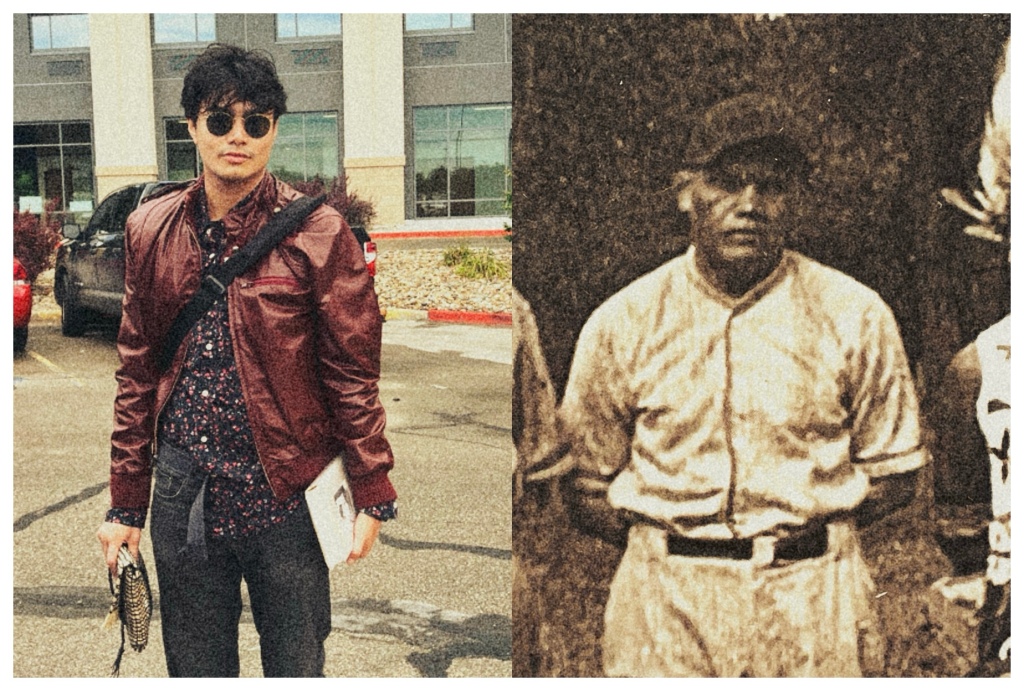

I’m careful talking about my family because you don’t deserve it. You don’t. I don’t know you like that and you don’t know me like that. In a world full of Indians trying to make it on TV, Indians watching Indians on TV, Indians who aren’t even Indian at all and we find out in the worst, ugliest ways, after those of us who fell out of community bared our very darkest selves to them, thinking they understood, I drag the dead weight of my unknown grandfather forward like a leash on a sick dog. There’d been a time when I was hungry, mad with obsession over this man who never claimed his children. I needed to know what he was so I could know what I was. Then I realized I never crossed his mind, would never cross his mind. I was a non-entity to him. He had impregnated a beautiful woman and left her like he probably had done a zillion times before and that was that was that. One night with the wrong man makes a girl a martyr, and the American Indian Movement was full of martyrs.

Besides, it wasn’t like this guy was my only tie to my… what? Ethnicity? Political affiliation? Full time god damned job? I knew who my biological grandma was. I knew she was gorgeous and sad. I knew she was strong. She used to be a bartender and ran with my other grandma’s siblings’ friend group. They said she was funny and hot and charming. They said she knew how to beat the shit out of someone in a way that changed the course of their life. They said a lot of the men followed her around like puppy dogs. I knew she died the same day I left Ithaca in a hurry. I knew I didn’t matter to her at all, but that didn’t stop her blood from being inside me any more than it stopped me crying over her for days. I know my real grandparents, the ones who raised my dad and worry about me all the time and give me presents and get on my nerves. I know my Papa Vince and my Grandma Gail and my Grandma Rose. I know if you’re not Native or of some adjacent cultural background, you’ve been counting up my Grandmas and trying to figure out how I got so many.

So you can imagine why, after my biological grandmother’s death, it’s been surreal to have so many people coming out of the woodwork at me to tell me who they think her babydaddy was.

It had been a little over a week since Deanna’s funeral. I was going to be crammed in a car with my mother, my little brother, and my little brother’s fiancee. We were going to Meskwaki Powwow. The Meskwaki Nation and I are on weird terms. I bear their name but not their status. I’ve written about this before. I’m more than happy to be a member of the White Earth Band of Minnesota Ojibwe, but the rules by which the Meskwaki Nation permits or denies their children continue to be a hot-button topic for the Fox people. Still, the Meskwaki Powwow is legendary for its rich history as an act of resistance and joy in the face of annihilation.

Dr. Charles Eastman, Dakota missionary for the YMCA recalled back in the late 19th/early 20th century, that, “One of the strongest rebukes I ever received from an Indian for my acceptance of [Christian] ideals and philosophy was administered by an old chief of the Sac and Fox [Meskwaki] tribe in Iowa.”

The elder had patiently sat through Eastman’s 1895 plea for Indian reformation and conversion before replying, “The white man shows neither respect for nature nor reverence toward God. You try to buy God with the by-products of nature. You try to buy your way into heaven, but you do not even know where heaven is. As for us, we shall follow the old trail. If you should live long, and some day the Great Spirit shall permit you to visit us again, you will find us still Indians, eating with wooden spoons out of bowls of wood.”

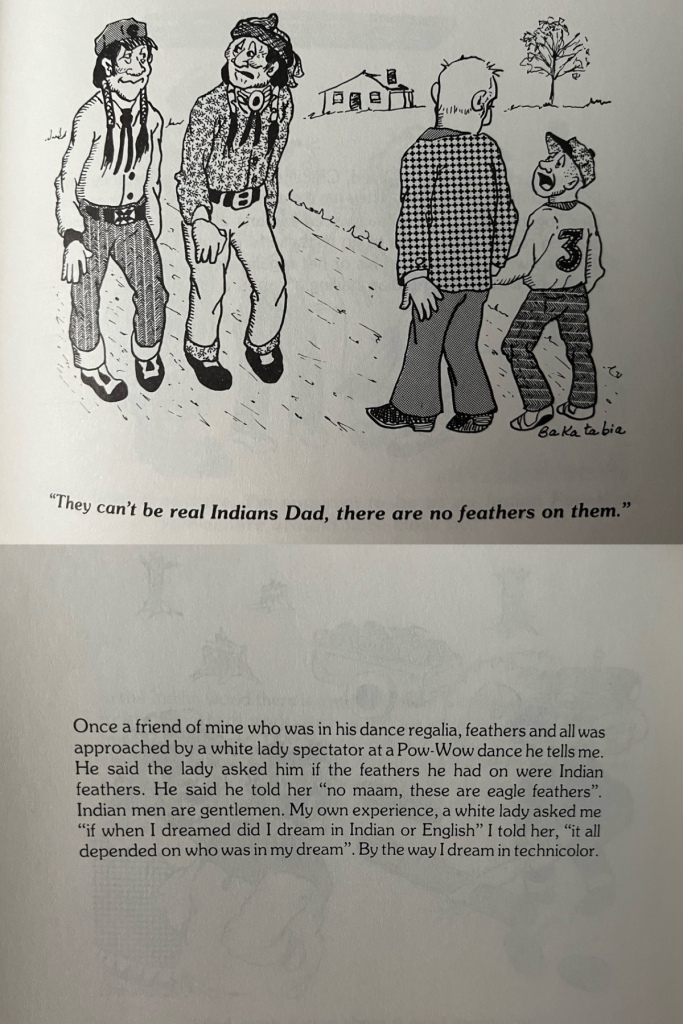

Eastman’s personalized call for reformation was partially due to the fact that the Meskwaki Nation’s response to the Religious Crimes Code had been to throw the biggest, most Meskwaki party ever. They held sporting events, group harvests, dances and art fairs open to the public until Smallpox decimated their village, prompting the U.S. government to burn said village to the ground and replace it with isolated houses, far away from one another. In 1913, the newly spaced out Meskwaki Nation renamed their harvest the Meskwaki Powwow, and invited outsiders to come celebrate. Performance has been a vibrant tradition with my mother’s tribe, and one of our ancestors even rode with Buffalo Bill back in the day as a career Indian. The Meskwaki mastered the art of double-speak—giving the white man one story while giving themselves another in the same exact breath.

Still Indians. We rolled into Meskwaki Nation and I melted into the familiar heat of it. I’d lived here as a small child and could always bear with the summers in a way I couldn’t elsewhere. I was happy to note this hadn’t changed, even with the world on fire. The trees and their knotted red trunks twisted up into the vast blue sky, their tiny green leaves shimmering gossamer in the soft breeze. Bitterness spiked, unexpected, at the back of my ribcage when I realized I’d need to reintroduce myself to people. When it hit me that this wasn’t mine to keep. I shook it off, that horrible, colonial sense of scarcity, and did my best to keep it at bay, even when my family spent my patience. Even when the third or so person asked “Where’s Chloe?” and I had to clench my jaw because that wasn’t even my deadname. Even when one of my mother’s family friends asked me both times when I showed up at his stand, “Where are you from?”

After we got some good Young Bear frybread, I realized I’d had it. I stood up and informed my family I’d be going on a walk to decompress.

I walked, aimless, for awhile. One of my friends was there because she was Miss International Two Spirit and was on the powwow trail as part of her regal duties. I wanted to see her but I also didn’t want to bother her. My extended family was everywhere, looking like me but brown, bearing our name. I didn’t want to bother them either. My mind was a ticker-tape of insecurity and I was so totally sick of it. I can’t deal with insecure people. It’s like, my biggest turn-off. So to be in the body of an insecure person gave me the ick, big time, but for the one person I couldn’t reject: myself. Eventually I wandered back to my mother’s friend’s stand. For the sake of the story, lets just call him the Artist.

The Artist’s partner is a gorgeous Native woman, we’ll call her Jay. She smirked up at me and then at her man. Behind them sat a third Indian I did not recognize.

“You gonna ask him where he’s from?” Jay sniped. “Again?”

The Artist shook his round head. He had pleasant features, curved and sloped all over, kind of like a turtle. His smile reached his eyes but only crossed half his face, like you’d caught him mid-thought and he didn’t want to tell you about it.

“Where you from?” asked the guy in the back. He was wearing sunglasses and grinned at me, pretending he was in on the joke when he wasn’t.

“My father’s from White Earth,” I said. “My mother’s from here. You know her.”

“I do,” said the Artist, laughing in the way everyone down there does when they think about my mother. “As a matter of fact, I know your father, too.”

“Oh?”

“Yeah. Your ma hauled him over round my place, oh, about twenty years ago now. Wanted to know if I was his dad.”

I stared at him, this small, round-faced man with no discernible features in common with me or anyone related to me, least of all my dad.

Jay raised her eyebrows at her man. The guy in the back had checked out the moment his joke didn’t land.

“I’m not, by the way. In case you were wondering.”

“But you could have been,” said Jay. She didn’t say it accusingly. If you’re dating in Indian country it’s like that. I already told one of my friends back home they can have me after my first divorce. Maybe my second. Even with so many of us being Christian, we just sort of have to be cool with people, well. Hitting it raw before they got with us, you know?

The Artist nodded, then shook his head emphatically. “Okay, well, I did, you know… I…”

“You got around,” said Jay.

“I got around! Didn’t we all? But I’m not his dad… or, his dad’s dad. I can’t be, I…”

The guy in the back, smelling blood, put down his phone and tuned in. “Huh? Who’s this kid again? He lookin’ for his dad? Are you his dad?”

“No!” the Artist yelped. “I’m not his…” he looked at me then, “I’m not your dad! And I’m not your dad’s dad, either.” He took a short, jittery sip of his pop and let his eyes unfocus. He jabbed one callused finger out, partly at me, partly at someone only he could see. “You know, I’d bet you I seen your grandfather, though. Or who he could be. A potential. See, I was at that protest. Summer of 1970. July. I was supposed to, you know. With this girl. But I was at a protest instead. And then you know who I come upon is this Oneida girl. I think she was Oneida, at least, I can’t really recall. Couldn’t have been taller than five two, five three at best. Backseat of a station wagon with this big guy from way over in Pine Ridge. Giant man. Two of them goin’ at it at that protest. And I’ll bet you anything that’s your grandfather.”

I blinked at the Artist. The meanness in me was new yet, but I could feel her curling around my tongue, ready to snark, “But I don’t wanna be from Pine Ridge,” knowing damn well I’ll be canceled for saying that, knowing every Indian I’ve shared this unsaid whiny rebuke with found it funny as hell anyways. Instead I said nothing.

The Artist nodded at me again, his brown eyes firm and intense with the “how-it-is” of it all, the surety that he’d solved some decades-old mystery, right here, never mind that he just told some kid he barely knew the story of the kid’s father’s conception. Like, ew.

“Look into that,” said the Artist. “Big guy from Pine Ridge. He mighta been six foot seven.”

“You, uh, you got a name?” Off of him shaking his head, “or, uh, literally anything?”

“Nah,” said the Artist.

Awkward silence. Then the guy in the back gestured to where there were two bowler hats with beaded hat bands on display on the table.

“You should buy one of these,” he said. “You have the head shape for it.”

“That’s okay,” I said, already drifting away. Then I walked backwards into a world where I hadn’t heard that story, a world where I was just some guy in a long line of “just some guys,” all the way back to the lucky bastards who got to live in a world where our people weren’t batshit crazy all the time, in a world where we could eat our ash bread and our tuber and berry soup with wooden spoons and wooden bowls.

Part of my obsession with the unknown grandfather has to do with my own mortality. My mother’s side, both sides, all sides, tend to live well into their eighties and nineties. People were shocked when my father’s mother made it as far as she did. Apparently she was the last one of her siblings, a fact tragic both in its finality and my cold tone relaying it. I should care more. I do, it’s just that she and her siblings exist to me the same way parallel universes do, or Imagine Dragons. Like, I could tell you all the words to Radioactive, but I don’t really feel it the way the average American Eagle centrist Protestant feels it. Fuck. I don’t think I’m putting that sentiment in the final post. Or maybe I will, just because I need you to know that I kind of suck. I’m bitter and lonely and part of me will always be that little girl, staring at a picture of an old, hard, martyred woman on her father’s phone, knowing with a deep, irreversible sense of betrayal that that was his mother and that she would not be in our lives.

Therein lies the other part of the obsession. That little girl realized it takes two people to make a baby. Therefore the other half of the equation was still out there, somewhere, maybe capable of loving his child. Maybe he could be convinced, once he saw how cute and sweet and special his three little grandchildren were. The girl I was prayed for that, even though she knew by then and I know by now that men are fickle and infuriating, and Native men doubly so.

I have, however, inherited my father’s handwriting. That thing everyone calls chicken scratch because it is. I used to have “pretty girl handwriting,” the bubbly, big-looped lettering you see in the notebook of a girl who tries hard and gets results, even though I did neither, but now that I’m a Native man in a big city, I’ve become his echo. It makes me wonder how much of his personality, how many of his traits, came from these two strangers. There is the daisy-chain we’re tied to by what the anthropologists call “fictive kinship,” and then there’s all that blood.

The funny thing about genocide is that you can’t remember anything before it. Everybody who could have told you what was what is dead now. Been dead. Murdered or disappeared or incarcerated or maybe they just never returned your dad’s calls. The funnier thing is that the people who killed your grandparents are still alive. They have houses and incomes and children and grandchildren and great-grandchildren. Some of their grands are your friends. They share Mary Oliver posts about letting the soft animal of your body love what it loves and brand themselves with Tove Jansson, mushroom philosophies, esoteric ramblings, God. The by-products of nature, buying their way into heaven. Perhaps the funniest thing of all is that you have to be civil about this. You can’t just remember everything and take it out on them. Sins of the father or whatever. You have to look them in their wide, blue or green or grey eyes, and you have to hum in soft acknowledgement when they tell you about how they’re on some great and beautiful journey, how they’re really trying to find what works.

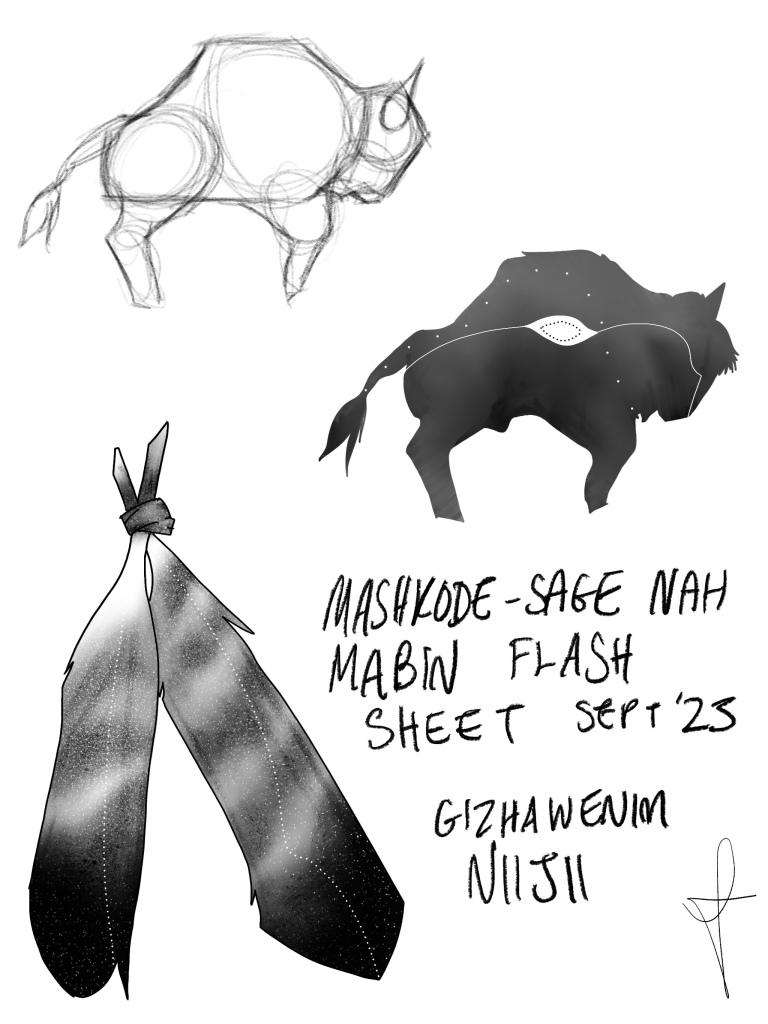

Back at the Watershed, I sat across from Taylor and sketched a tattoo commission for Mashkode-Sage in silence. She had asked for golden eagle feathers and a buffalo. “You know the kind.” Back when I’d crashed with her on one of my uncountable trips across the country, she’d said she was pretty sure she was done with tats. I nodded at that; she had a healthy assortment. Me, I want more. I keep telling people I look like a child scribbled on me with a Sharpie and ran away. Smokii said, “Yeah, that’s what it looks like when you don’t have money for tats.” He snorted and I mentally filed the exchange away for when I wanted to hurt myself later for doing everything wrong and out-of-order.

That’s one of the things I like most about Mashkode-Sage, actually. She will make these hardline declarations and go back on them when more of the narrative unfolds. It makes me feel dynamic by association. Like her ability to grow and change is somehow talismanic with mine.

She is also the child of an adoptee. She writes about it in her own words on her Instagram. Like this, we understand each other.

I do commissions infrequently. I think part of me still feels guilty for every time I dropped the ball, going all the way back to the fifth grade, so I punish myself by keeping my talents close to my chest. If I don’t set up any expectations, there’s no way I’ll let people down. But there, in the Watershed, the goddamned folk band wailing away, I felt like this could be something I could do. This could be income.

I finished the two feathers with a flourish. Pride warmed me and I showed Taylor, practically vibrating with it. Then I started in on the buffalo.

A long time ago, we went to the Hearts of Our People exhibit at the Minneapolis Institute of Art. Few pieces resonated with me as deeply as Dana Claxton’s Buffalo Bone China, released the year I was born, which consists of a short experimental film projected above a pile of shattered bone china, reminiscent of that one photograph I refuse to share because it makes me sick. You know the one. Throughout the video installation, there’s a repeating clip of a herd of buffalo running. The rhythm of the soundscape and the repetition grinds it into you: these are People. Their enormous heads mopped with thick bangs over high, severe cheekbones and deep, wet eyes. Their arms and their legs and their broad shoulders. They dance like we dance. Their rage and love are ours. I don’t know how long I sat in the blue dark, watching them. Trying not to cry because I didn’t want one of the many, many white women who’d been filming my journey through the gallery to find me and capture my noble savage grief on camera.

As if I’d thrown it in the freezer that day and only now rediscovered it, the feelings came back full force. This time there would be no context for the outsiders to latch onto. I would be just another white boy in a bar, upset and lonesome, blinking at the wall. I traced my sketch of Mashkode-Sage’s buffalo until I felt something spring to life in the cold, digital slab. Then I did the line-work and, with a shit-eating, manipulative grin, added a penis so the buffalo could reproduce.

I stole my insistent terminology, “martyr,” from Carmen. We’d been up late in her apartment again, talking for hours, and somehow got on the subject of the American Indian Movement. All the unclaimed babies it made. Most of the secret-not-secret stories about AIM are shared like this. Two women talking after midnight, their legs almost touching, their eyes on the wall or the floor.

Both of the horror novels I’ve read this year, John Darnielle’s Devil House and Gus Moreno’s This Thing Between Us, blend genres and interrogate ethics. What are our responsibilities as writers, as storytellers? What comes through when we violate these unspoken contracts? Sitting down to write this, I was faced with the problem countless Native writers before me have dealt with since the moment you demanded an explanation. When does this stop being my story to tell?

Maybe it stops here. Maybe I’ll leave you with the image of me and Carmen, mere feet apart, talking about the men who, by their own narcissism, caused our respective dynasties to exist. Rootless or headless, but extant nonetheless. Sure, most tribes, like the Meskwaki Nation, require proof of paternity to enroll a child, so if your dad bounced, or better still, never knew you even happened, you’re fucked on the federal recognition front. And sure, a lot of AIMsters justified their anti-birth control stance as being part of some great repopulation initiative. Never mind that all they needed to make a person was a station wagon and a protest, while their women had to give up the rest of their natural lives, had to face the government’s insistence upon stealing and trafficking their babies to Christian homes who did everything you could imagine and more to the poor bastards.

But someone clawed their way out of there. A couple someones. Scarred and burnt and ugly and alive, these kids grew up and struck out and had kids they claimed, kids they kept, kids they raised in whatever approximation of “our ways” they could manage.

Or they didn’t.

Sometimes I dream about the ones who didn’t. I have an aunt I visit with in dreams, you know. She’s got ash blonde hair and pecan brown skin she tries to bleach. She wears a little gold crucifix around her neck that she clutches whenever she sees me. She says I must be the Devil. That I’m here to do the devil’s work. We walk through a forest that will never see the light of day. Thick, ropy vines hang from the dark green canopy, exposed blood vessels threading the telltale heart of her pain. I don’t confirm or deny her accusation. I just walk with her, my bare feet in the spongy earth.

One foot in front of the other.

I am the father and the Mother’s brother’s distant cousin / the children and the wives / a multitude of thousands live inside my head, manufacturing weapons, demanding to be fed.

David Keenan, “Me, Myself, and Lunacy”

Leave a comment