Certain places we cannot return to. The coordinates remain, the address is the same, but the context has changed. Whoever we occupied these spaces with, whatever we were going through at the time, the moon’s apogee, the temperature, whether or not the ground was wet or dry, all of this decides and defines the place. You know what I’m talking about. You can’t go back to high school, for example, even in dreams. You’ve hardened and cracked and hatched. You’ve grown and changed.

One such absent place, for me, is the porch where Lily Gladstone first told us she was going to quit acting.

Hot summer’s day bled into brittle night. The sun lowered behind the Rocky Mountains like a wounded animal. A bruise spread across the sky. I can’t recall if this was the old house or if our elder had moved already. The old house and the new house have similar porches in the dark. Besides, if you’ve been keeping up with the press, they all say it’s hard to look away from Lily when they’re talking. That TikTok of Martin and Francesca Scorsese, “she consumed,” comes to mind. So we sat on the porch, I at her feet like an overgrown child. A cherry burned in her mouth and then between her fingers as she jut her chin out at some dying future. Waved it off.

“This isn’t working,” said Lily. “So why force it?”

What struck me in that moment was their tone. Their head’s always been screwed on real tight, as they say, plus a total lack of desperation. There was no self-pity or wallowing when she spoke. Lily was like a mechanic under a carriage of dwindling opportunities, sliding out from beneath the machine and shaking her head. Not worth the effort or the cost of materials to fix. Sorry. Better get you a new car.

Lily took another languid drag of her cigarette and chuckled. I looked at her carefully. There are people on this planet who electrify and magnetize. There are birth lotteries and hard-won victories and debates about who deserves what. My favorite thing to hear is, “You’re not special.” I was raised in houses of fast-paced discussions and constant commentary. Our late mom Carol, who was alive on that porch with us, would get into it with our dad, Shaawano, about the concept of “deserving.” I don’t remember who took what stance. I just remember drawing my own conclusions. Nobody deserves anything. That’s not nihilism. What I mean is if you get in a terrible accident, if you get an STI or your dog dies, you didn’t deserve it. God’s not punishing you. And if you get ten thousand dollars in a tragic windfall, you didn’t deserve that, either. Someone made the decision to write you into their will. Someone loved you. Does that make sense?

We watched Lily decide her life wasn’t going how she wanted or planned it. We listened to their low, earthen drawl. We were on their land. You could see Chief Mountain if you slanted your eyes toward Lily’s shoulder and darted them out to your right very quickly. There are the places and then there’s the imagined future where we tell someone about the places. In that moment I was in love with some girl back in Wisconsin, I think, and half my time was spent fantasizing about how best to describe the big sky to her. I wanted this girl back home to fall in love with me because of how much I loved the big sky, how the big sky seemed to love me. That future died, too, or never happened. I couldn’t bring myself to speak to anyone about these summers. I still can’t, not really. That’s okay. But that’s how I’m able to remember all of this so clearly.

Lily planned a graceful pivot and allowed herself a few minutes of mirthful bitterness. A working actor is like a desert island. Every audition a message in a bottle. Sometimes the rescue doesn’t come. She finished her cigarette. We all saw the metaphorical door close.

Years passed between the first resignation and the famous one. Mere months after the porch, Lily was cast in a highly-anticipated Kelly Reichardt project, Certain Women. We were so proud of them. I told and retold that story, the story of how Lily quit acting and then got a big, important role. When Certain Women went to streaming, it was a goddamn event. All of us stood in one of our siblings’ living rooms—whoever had the biggest screen and the best sound system at the time—and sat through two hours of grim, contemplative Montanan drama. Lily garnered some accolades for her performance, well-earned, and then the No DAPL protests pushed Indians into the mainstream. It seemed every chimookomaanag who’d ever called themselves a producer wanted to sink their talons into Lily. Projects were thrown her way like a cat offers carcasses to its owner. Will you eat this? Is this good for you?

I moved from New Mexico to Seattle. Roomed with my sister Lacey and her kids. This was 2016. I’d recently shot a sizzle reel for a project—Six and Bisti—which has transformed from a Spaghetti Western into something deeper, what I’ve been describing for about five years now as “a love letter to our ancestors.” This is my shameless plug for Tse’Nato’, by the way. Make of that what you will. Anyways, I was eighteen going on nineteen. Lily Gladstone was sometimes in our house. My nieces were five years old and three years old. One shared a name with Lily, so we differentiated with a nickname I won’t tell you because it’s ours. Lily chased the girls—shrieking with laughter—around the tungsten suburban purgatory we occupied (yet another place none of us can return to) and when it was the girls’ bedtime, Lily sat on the back porch with us. We told each other stories. About half of my adulthood memories of Lily are either on the porch or in a park. It’s almost always nightfall.

“Because Native people are trendy now,” Lily had said during one of these late-night talks. “I’m busy.”

I wonder what happens to all the aborted films. I’d auditioned for a few, back when I was pre-transition. Always the same role: over-sexualized Native girl gets brutalized on camera and dies. Murder or exposure. One role went to another friend of ours, someone more successfully female, but besides her frigid midwinter selfie, I never heard any more about it. Thank God, though, because she’s had a much better career since.

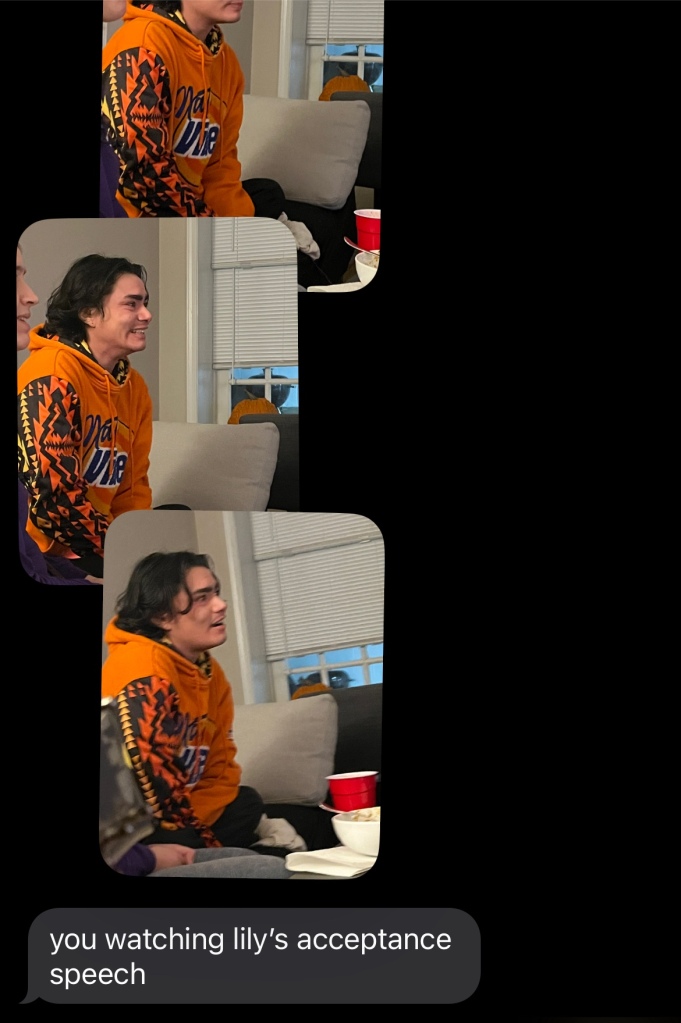

I had a dream last night someone asked me where my film went. I said “it’s in development hell” and they laughed. Then they asked if I believed it could be raised from the inferno. On the far wall, Lily’s Golden Globes acceptance speech played on loop. I nodded.

“A lot of things are possible now,” I said.

Because of Lily Gladstone, I tend to call everyone by their full names. Part of the reason is because I think it’s funny. Ellie Hyojung Lee was in my house the other day and said, “You name drop all these people in a way that makes me think you’re referencing like, a famous person, but it’s always just some guy.” That’s the other half of it. When you’re on a porch late at night with Lily Gladstone and they’re telling you something important, you realize all at once that you are privy to some machinations of human history. You can reach your hand out and feel the fabric of spacetime warp. There is a man behind the curtain, kind of, and it’s you and your kin. The sacred task is to remember that this person, this brilliant, furious, hyperactive, bizarre and beautiful person, is also just some guy.

I’d be remiss not to tell you, then, about Erica Tremblay.

We were deep in the pandemic. What we didn’t know was that there’d be a moment, three years from now, on live television, where our loved one would look across a glittering sea of drunken stars and stare right into the eyes of the greatest living director and, voice thick with affection, call him “Marty.” No. At that time, we were all, including Lily, just doing our best. I had long since quit the film industry. Instead I built robots for a living on the edge of Ithaca, New York. Carol had died almost three years prior, in July of 2018. A month after her, our friend Leilani, who Lily also once taught, passed on. Then our grandfather. A new trio of deaths had just begun in 2021, but I didn’t know that yet. Erica—who is Seneca-Cayuga—lived on her people’s own land due to a series of strange coincidences. That’s her story to tell. Lily knew Ithaca well—she had apparently stayed with my parents for a brief period of time, but that’s their story—and decided to put Erica and I in contact.

Erica and I went for a long walk through Cascadilla Gorge. I loved her right away. Her eyes are difficult to describe. Sometimes they’re ice. Sometimes they’re the waterfalls of her homeland. Usually they’re sharp and conspiratorial. She and Lily have the same wry undercurrent when they talk about the lives they lead. A very low bullshit tolerance and a very high regard for what’s real, what my Tuscarora friend Meredith’s child calls “for real for real.” At the time, Erica and Lily were writing their feature length collaboration, Fancy Dance. Erica asked if I could play Lily in the Sundance screen test. My dad would play Lily’s character’s adoptive father. We agreed to it.

Life happened. Dad moved out of Ithaca in 2021, back to our homelands. I stayed. Got black mold poisoning. Followed him. Moved to Baltimore in October of 2023. Gave away my laptop. Watched Killers of the Flower Moon twice, both times at the Charles Theatre. Got a free laptop from Erica that I used as the centerpiece for my home desktop setup. Started to write again. Remembered to breathe.

When I was little, I learned about “all my relations.” I tried to imagine what that could mean. Before I’d been given that teaching, my dad told me that if I ever had trouble falling asleep, I should start listing off everyone who loves me. I stopped doing that pretty much as soon as I started because I’d get overwhelmed and begin to cry. But here both lessons come to mind. There are all these filaments coming out of my heart right now. I asked Lily—didn’t even congratulate her, by the way, which was literally so crazy of me (but I guess this is kind of a congratulations)—for their consent to write about them on this website. I asked Erica, too, and then I texted Grant Conversano, a filmmaker I met out in Camden, Maine, at a CIFF screening pre-pandemic. This next part of my ramble has a lot to do with them.

One of the big things I was most excited about when I moved to Baltimore in 2023 was my proximity to the train station. I can go to New York City basically whenever now, though I’m such a homebody, you have to dangle a carrot in front of my face to get me to leave my intensely curated apartment. Around the time Killers of the Flower Moon came out, my carrot was a meeting with Nara Milanich. We were gonna talk about her followup to 2019’s Paternity: the Elusive Quest for the Father, and on a whim, I texted Lily Gladstone: are you in nyc rn?

Their quick reply: Are YOU in NYC right now?!?!

After a nourishing meeting with Nara, I found Lily and her college bestie Gillian in Central Park, right next to the carousel. There’s something here about cycles and horses. A sharper eye than mine might be able to hone in on it. We walked and talked and sat in the dark and talked. We joked, all three of us, about “the new normal” bearing down on Lily. We laughed. Lily showered me in little trinkets because I was having a flareup and their immediate response was to scurry to and fro until they assembled a care package. I love the articles I find that mention this quirk of theirs, the way they’ll sometimes move from room to room like a little kid showing you their toys for the first time. Then they’ll soften and grow serious, their luminous face changing planes. Shifting gears.

We entered the subway together and they handed me a KN95 mask, marbled in the same colors as my apartment. Of course, I didn’t tell them this. I just let my jaw drop a little. They put on a matching mask and said, “So people see we’re friends.” I had run out of words at this point. I just kept saying I missed you. I missed you so much.

My friend Charles, who performs harsh, experimental noise under the name FLOSE, had a show in Brooklyn the next night. A friend of mine from Ithaca, Han, was going to meet me for tacos beforehand, Charles being their roommate and all. I told Grant Conversano where I was and they found me after the FLOSE set. I’d tried to stay as long as possible, but the subwoofers turned my stomach. I’m stone cold sober and here I was, staggering out of a bar in Brooklyn on a Tuesday night. Conversano followed me out and I collapsed into the heavily graffitied outdoor seating area. Their hair was long, flowed over their shoulders. They watched me with an unreadable expression.

“Hold my hand,” I said.

They held my hand.

“It’s not just the harsh noise,” I said. “At least, I don’t think.”

“I know,” said Conversano.

They’d gone through something similar. When they were around nineteen, twenty years old, one of their close friends had also been swept into the tide of fame and prestige. One minute you’re in an empty field with someone you love and the next minute, they’re nominated for a Golden Globe or an Academy Award. Nausea had overtaken Conversano, too, a placeless, sourceless nausea. Their friend was an actor. Conversano is a director. There was no jealousy, no obvious reason for this sudden, full body illness. Not jealousy but magnetism. The tremendous, crushing weight of a vibrational shift, of contexts changing and histories being written and rewritten. Doors closing. Doors opening. I imagined a gigantic alien ship with a tractor beam. How it comes into our field and chooses who it chooses. Takes who it takes. And there you stand in the crop circles, staring up at the sky as your friend is carried off. The big sky.

My father had me read Foucault’s Panopticism when I was like, twelve. I met Lily Gladstone shortly afterwards. Red Eagle Soaring has a summer program called SIYAP. They hire working artists to come wrangle all us shitass kids. Lily was one such unfortunate soul. I’m kidding. She held her own. We loved her. Obviously we still love her. We were also shitasses.

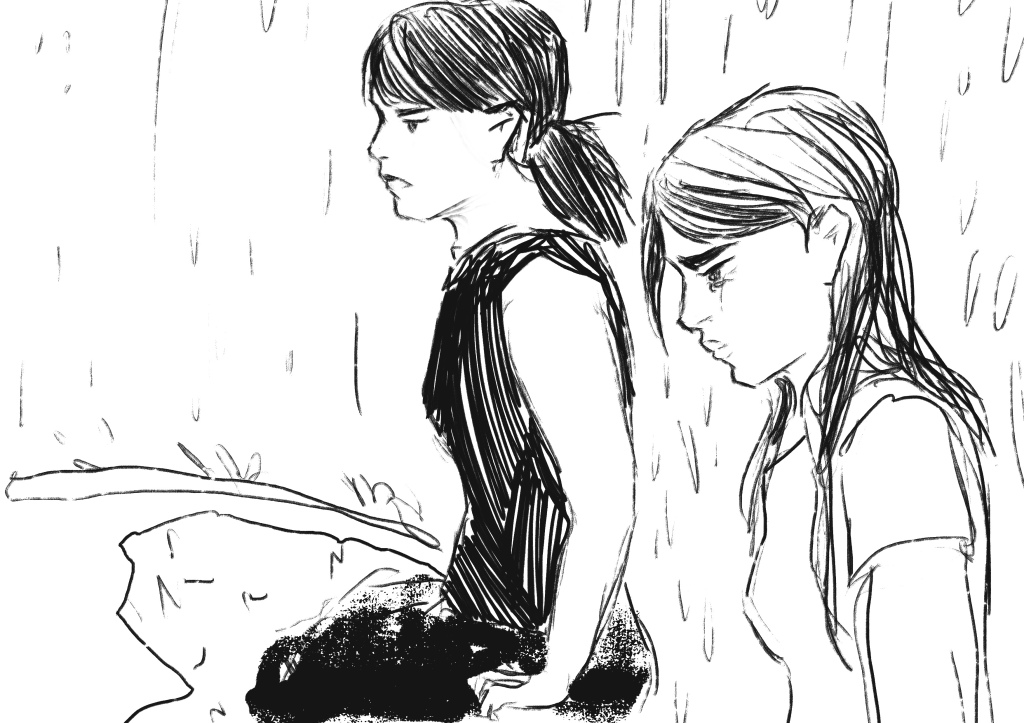

One summer, there were all these child psychologists around. They kept taking notes. They were white. I have always had a terrible ability to pressurize a room when I’m angry or upset. I suck the life out of everything and drag everyone else down with me. I do this less and less the older I get, but I still have my moments. That summer was no exception. I hated being surveilled and I hated being annotated. I ruined the vibe as thoroughly as I could. The sky above Daybreak Star Indian Cultural Center opened up and a torrential downpour began. All day just grey and rhythmic. A thousand tiny water drums. I scrambled up the round staircase and into one of the empty rooms we had smaller workshops in. There was a faux polar bear rug in the bay window and not much else. I sat down and ugly cried. Ashamed of my behavior. Ashamed of this terrible, awful thing inside me, this monster I swore lived just beneath my skin and pushed at my ribcage.

About five minutes into my meltdown, I heard the heavy pneumatic hiss of the door as it opened and shut. Lily crossed the big room in a few firm steps. They sat next to me, on my right. We were silent but for my occasional sniffle.

I won’t tell you everything they said. I was sixteen years old. I was the worst person I knew. I dreamt of blood, fire, men with masks and guns. I dreamt of war and famine and plague. I dreamt of things bigger than I could comprehend, things so bright, they burned through your eyelids. Lily had bangs back then. Her hair was in a ponytail. She wore a black tank top, black pants, and black shoes.

“There’s a paradigm shift coming,” Lily said. “Do you know what that means?”

I nodded. Kicked my feet against the wood slats.

“It’s gonna hurt,” said Lily. “It’s gonna hurt because healing always comes with hurt. Growing pains. It’s just growing pains.”

Ten years later, I lay on my back outside a bar in Brooklyn and held Grant Conversano’s hand.

“I had a hard time,” Conversano began, “growing up in the South and hearing everything was part of God’s plan. It felt unfair. Why would God listen to some of us, but not others? And you know, they say God’s plan about everything. The best and the worst.”

I hummed. “Your hands are soft.”

“I get that a lot. Apparently it’s a sign I’m untrustworthy.”

I laughed. Brushed my fingertips across their palm. Some of their memories flashed across my eyes. I knew they were theirs because I’d never seen trees that particular shade of green before.

“It’s not God’s plan. It can’t be. It’s all… chaos. Some of us are born, you know, into the worst conditions. We live for a short, hellish time and we die horribly and we never find out why. And then some of us are told from birth that we’re special. That we’re different.”

“The accident of your birth,” I said.

“Exactly. So we can’t dwell on these things. Don’t get me wrong, sometimes I find myself sitting somewhere just asking something dumb like, ‘why do I get to have so much fun all the time?’ But we can’t lose ourselves to this idea that there’s some inherent specialness. These things just… happen how they happen.”

“And you have to deal with it.”

“And we have to deal with it.”

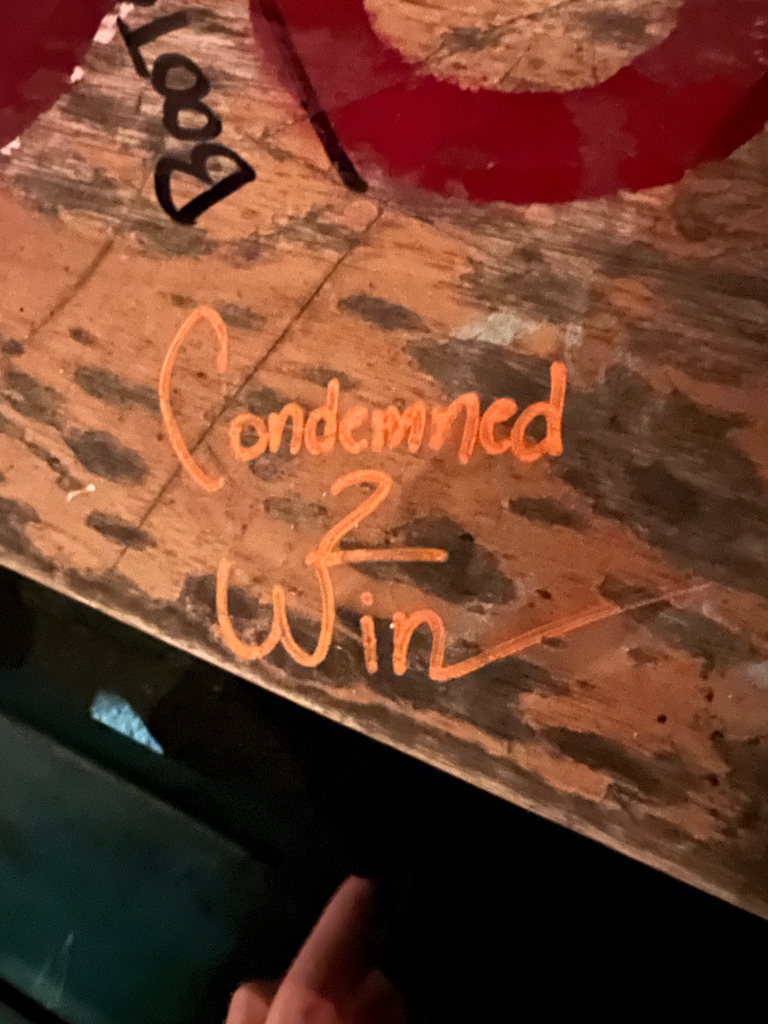

I sat up. The nausea subsided. On the table between us, someone had written in sun-yellow marker: “Condemned 2 Win.” I stared at it a long time. Hammered my knuckles against the wood. Huffed, an ironic grin across my face.

“You are all so lucky I’m not insane,” I said. “All these patterns.”

My heart hurt from only seeing Lily for what felt like a split second. I filled the absent places with more questions. I wanted to hear more about Conversano’s life. Where are you going? What are you doing now? Who are you on your way to become?

I walked them home. I lingered. Not God’s plan but whatever it was Lily saw on that porch. A future like a broken machine or a boat dead in the water. Closing the door. Saying no. Saying not right now. Knowing when to quit and when to get back up again. When to hope. When to keep the faith.

There are things I haven’t told you. Things I will never tell you. One thing, though. A couple years ago, we were all in an auntie’s house. Me, my siblings, the kids, Lily, and Lily’s mom, Betty. I had no idea Betty wasn’t Native. That’s kind of a compliment, I guess. Most white moms are like, incurably white. Betty existed in the patchwork foreground, a gentle smile on her face as Lily and my sisters played with the kids and talked serious talk in equal measure. One of the little ones was going through a phase, something she picked up in daycare. You play a hand game with someone. One hand goes here, the other goes there. Three claps. Maybe four. I can’t recall all the details. But if you end the game with your hands crossed over each other, it means you’re “related.” Betty and Lily were there as our precious one, four years old at the time, crossed her hands over mine and cried out, ecstatic, “We’re related!” before tackling me.

“My mom’s name is Peace,” said Lily. “So my full name is Lily Peace Gladstone.”

Betty Peace smiled big and shook her head. There are places we cannot return to and I mourn it. Let the grief melt each moment into the patchwork memory. Let me live through this again and again but more importantly, let us live.

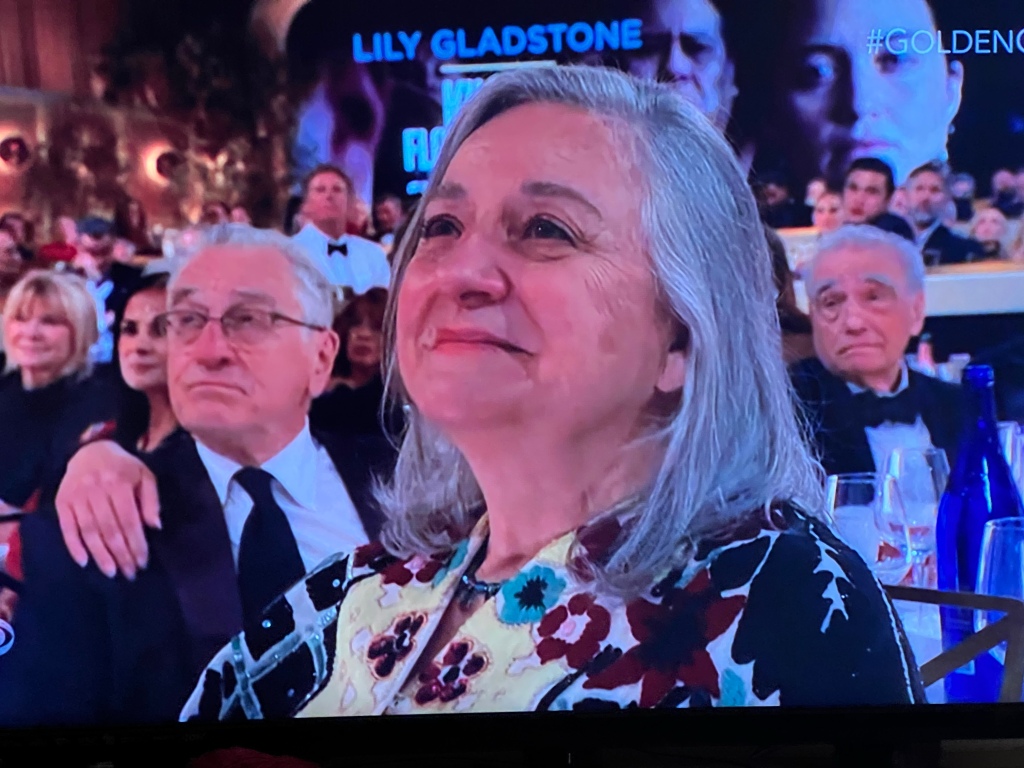

The Golden Globes videographer zooms in on a beautiful older woman. A big smile, long white hair, rosy cheeks. Tears in her eyes. High definition in the foreground while in the background, on her left and right, respectively, sit Robert de Niro and Martin Scorsese. Not God’s plan at all, but Lily’s. The indomitable drive of “just some guy” to accomplish what is otherwise considered impossible. The growing pains clarified in this one vibrant moment. I sat on Phil’s couch and cried happily while everyone in that vast, violent room stood up and applauded. I took pictures of Betty. Phil took pictures of me.

They used to run our dialogue backwards. Time runs backwards for me, too, sometimes, slipshod and adrift in the loom of the universe. The rain goes up, up, up and away into the grey clouds. The sun comes back from behind the Rocky Mountains and swallows all the purple. Smoke disappears into Lily’s hands and the porch gets brighter, brighter still.

“This isn’t mine,” Lily says, lifting a solid gold model of Planet Earth. “I’m holding it right now.”

They took the Indians in elder housing to see Killers of the Flower Moon the week it opened. My grandma called me up afterwards.

“Hey. Your lil friend did pretty good.”

I laughed. Grandma Rose has always had the uncanny ability to humanize the historical, to boil and reduce all we can’t hold into a few simple words.

“Yeah,” I said. “Yeah, so she did.”

Leave a comment